By Alexandra Moleski, NHD Program Coordinator

Kwaï! Welcome to National History Day in MA 2025! Here at the Massachusetts Historical Society, the NHD in MA team is getting excited for contest season. In preparation, we have been brainstorming topic ideas that relate to this year’s NHD theme, Rights and Responsibilities, to share with students as they begin their project research. I wanted to use this blog post to highlight some MHS sources that could inspire an NHD project. Choosing your NHD topic is a very personal experience, and with November being Native American Heritage Month, I thought this would be the perfect opportunity to explore sources in the MHS archives related to my own Wabanaki heritage.

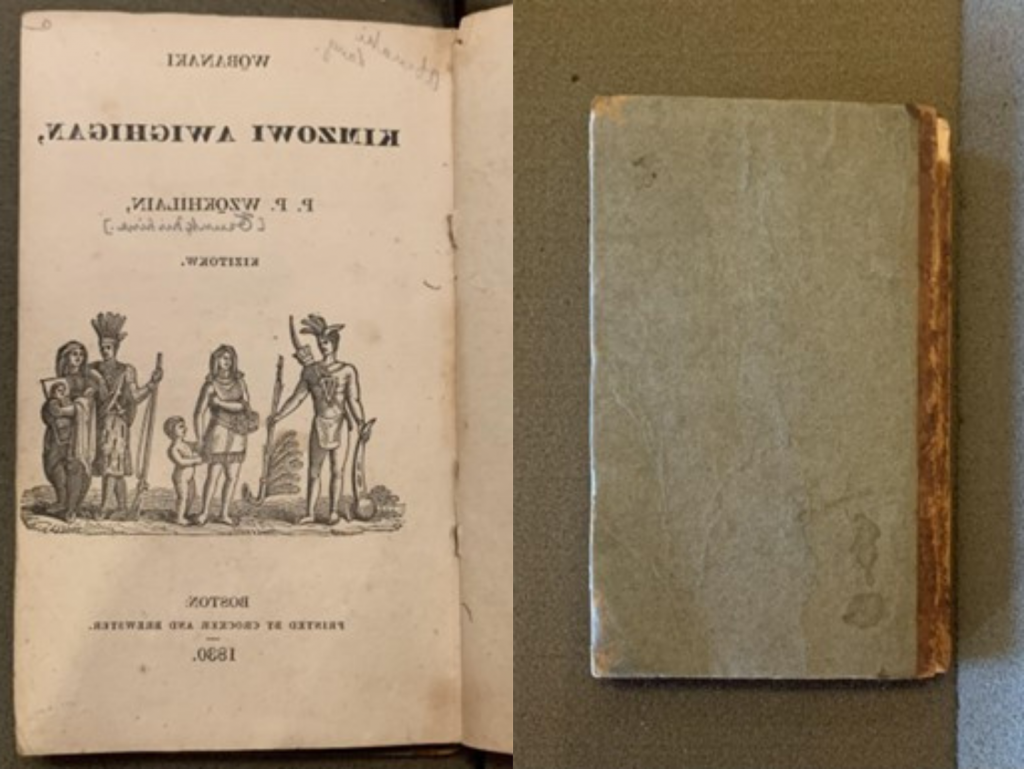

My search for Wabanaki history in the MHS collections led me down many interesting research avenues, but it begins with the 1830 publication Wo̲banaki kimzowi awighigan, which translates to “Wabanaki learning book.” The book is small and fragile–only about the length of my hand with a blank front cover that is flaking and detaching from the binding.

Despite its delicate condition, I was so excited to find this learning book and I immediately had questions about its origins, particularly its creators. It was published by Crocker and Brewster, a Boston-based publishing company that published many educational works throughout the 19th century. But who was the author, P.P. Wzo̲khilain?

At first, it was difficult to find consistent and reliable information about Wzo̲khilain because he was known by many names throughout his life. P.P. Wzo̲khilain is simply how his name was transliterated into the Latin alphabet for publication. While attending school, he would go by Peter Masta, adopting the last name of his stepfather. But his given name was Pial Pol Osunkhirhine, or Peter Paul Osunkhirine. Osunkhirhine was born in 1799 and grew up in the Abenaki community of Odanak, meaning “to/from the village,” which is in present day Québec, Canada.[1]

The Abenaki traditionally resided in what is now the northeastern United States and parts of Canada. In the late 17th century, displacement and continuous armed conflict between the British, the French, and their respective tribal allies, pushed some Abenaki to migrate to the St. Lawrence river valley and establish communities, including Odanak. And the Abenaki were not alone in seeking refuge at Odanak–the village was historically diverse, with as many as twenty different Indigenous tribal names connected to it at one time or another.[2] Residents even included European Christian missionaries and other colonists, some of whom had been taken captive by Abenaki in battle, but when faced with the opportunity of freedom, had chosen to remain at Odanak.

Just as there was a variety of people migrating to Odanak, it was not uncommon for people to venture outside the village as well. At age 22, Osunkhirine traveled 300 miles to Hanover, NH to attend Moor’s Indian Charity School, which was then operating as a branch of the more widely known Dartmouth College. At the charity school, Indigenous students were taught the liberal arts, sciences, European agricultural practices, and to read and write in English, but according to the school’s own mission statement, the purpose of Moor’s was “More Especially for instructing them in the Knowledge & Practice of the Protestant Christian Religion.”[3] Osunkhirine arrived at Moor’s in 1822 but left after a year due to a dispute regarding tuition payment between school administration and the funder of Osunkhirine’s tuition, the Society in Scotland for Propagating Christian Knowledge in the Highlands and Islands and the Foreign Parts of the World (SSPCK). In 1826, the SSPCK continued to pay tuition and Osunkhirhine was able to continue attending Moor’s.

While in Hanover, Osunkhirhine joined the Congregational Church of Christ and converted to the Protestant sect of Christianity. In 1829, he returned to Odanak and founded his own school, known around the village as the Dartmouth school, in which he taught Abenaki youth the English language and European agricultural practices, believing this would lead them out of the poverty that so heavily impacted Odanak. However, as an Abenaki man and a Protestant in a predominantly Roman Catholic region, Osunkhirine’s founding of the Dartmouth school came with many of its own challenges.

The SSPCK refused to provide long-term funding for the school at Odanak, claiming that its sole purpose was to support Moor’s Indian Charity School back in New Hampshire. Osunkhirhine then sought funding from the government of Lower Canada, but his attempts were blocked by a local Catholic priest who did not want Osunkhirhine preaching Protestantism. The priest would wait until the men of Odanak were away hunting to intimidate Indigenous mothers and prevent them from sending their children to the Dartmouth school. In response, Osunkhirhine rallied support from the chiefs at Odanak and once again appealed to the government of Lower Canada for funds to support his school. This time, both Lower Canada and the local Catholic priest agreed to Osunkhirhine’s school and his teaching religion in it, but only if he did not promote any one sect of Christianity above another.

Osunkhirhine was never deterred by the opposition he faced for his Protestant beliefs. In 1835, the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions named Osunkhirhine missionary to the Abenaki. Three years later, Osunkhirhine established the first Protestant church at Odanak. In addition to his 1830 learning book, Osunkhirhine would go on to publish the Ten Commandments, Gospel of Mark, and hymns in his native Abenaki, as well as theological essays in English.

So now we have uncovered a glimpse into the life of Pial Pol Osunkhirhine, author of Wo̲banaki kimzowi awighigan. But when I began looking into the author’s background, I did not expect my research to lead me to even bigger questions and ultimately, a discovery about our understanding–or misunderstanding–of Osunkhirhine’s native tongue…

Wli nanawalmezi!

[1] Henry L. Masta, “When the Abenaki Came to Dartmouth,” Dartmouth Alumni Magazine 21, no. 5 (1929): 303, http://archive.dartmouthalumnimagazine.com/issue/19290301#!&pid=302.

[2] Gordon M. Day, The Identity of the Saint Francis Indians (University of Ottawa Press, 1981), 10.

[3] Colin G. Calloway, The Indian History of an American Institution: Native Americans and Dartmouth (University Press of New England, 2010), 7, http://digitalcommons.dartmouth.edu/dartmouth_press/5/.